Injury risks of artificial turf in soccer

December 16, 2011 7 Comments

Ever since Astroturf was first installed at the Houston Astrodome back in the 1960’s, there has been much controversy about the use of artifical grass playing surfaces used in a number of different sports. The main issues relate both to ‘playability’ and the way that the surface properties affect playing dynamics, and to the risk of injuries occuring on artificial surfaces.

Ever since Astroturf was first installed at the Houston Astrodome back in the 1960’s, there has been much controversy about the use of artifical grass playing surfaces used in a number of different sports. The main issues relate both to ‘playability’ and the way that the surface properties affect playing dynamics, and to the risk of injuries occuring on artificial surfaces.

Despite this controversy, artificial surfaces have been used in a wide range of different sports and in some famous venues. In American Football, for example, the New England Patriots and the New England Revolution share an artificial playing surface at the Gillette stadium, whilst most field hockey games these days are played on an artificial surface.

In the UK, I vividly remember the early artificial surfaces used in football back in the 1980’s, when many teams dreaded the trip to Queens Park Rangers, Luton Town, Oldham Athletic and Preston North End on account of their ‘plastic pitches.’ At the time, most of the pitches were derided by football fans due a combination of their poor playability and recurrent carpet-burn injuries sustained by the players and they lost favour quickly.

I was therefore somewhat surprised to read on the BBC sport website that there are moves afoot for a return to the use of artificial turf in the Football League, headed by Wycombe Wanderers and Accrington Stanley. My interest was all the more galvanised by the fact that Wycombe play in the same league as the team that I look after, Leyton Orient. From the Clubs’ point of view, the argument for installing an artificial playing surface centres on economics, with artificial pitches being much easier to maintain than grass. In addition, it is easy to host other events at stadia with an artificial surface such as pop concerts and other social events. There are independent advocates both for the use of artificial surfaces in soccer, and against their use.

As a team physician, my immediate thoughts turned to the risks of injury when playing on artificial playing surfaces. There is no doubt that there has been an evolution of the quality of playing surfaces over the years. Astroturf, developed back in the 1960’s, was known for it’s somewhat abrasive properties, and the risk of ‘carpet burn’ injuries was all-too-apparent to anyone who dared to perform a slide tackle or similar manouvre on the surface. These were not the only injuries of concern on early artificial surfaces, and there were plenty of papers in the literature that reported an increased risk of other injuries on artificial playing surfaces (see Ekstrand & Nigg, 1989 ; Girard et al, 2007 ; & Steele & Milburn, 1988).

However, the modern third and fourth generation pitches are very different in construction and often promoted as possessing the same properties and injury-risk profiles as grass. For example, Dragoo and Braun reported that the overall injury rate on the new surfaces is comparable to that seen on natural pitches.

However, the modern third and fourth generation pitches are very different in construction and often promoted as possessing the same properties and injury-risk profiles as grass. For example, Dragoo and Braun reported that the overall injury rate on the new surfaces is comparable to that seen on natural pitches.

Therefore, it was with interest that I read a new review article by Williams and colleagues published in Sports Medicine in November 2011 of football injuries on third and fourth generation artificial turfs compared with natural turf.

The authors performed a literature search using Cochrane Collaboration review methodology to evaluate injury characteristics and risk factors for injury on artificial turfs compared with natural grass turf over a range of ‘football’ codes including Rugby Union, Soccer and American Football. The outcome measure used to assess each included study was the incidence rate ratio for injuries on natural and artificial turf, calculated using natural turf as the reference.

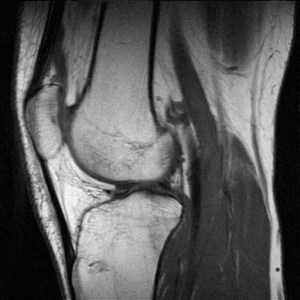

The authors found an increased incidence of ankle injury playing on artificial turf in 8 cohorts, although injury risk for knee injuries was inconsistent. There seemed to be a trend towards less muscle injuries playing on artificial turf compared with natural turf. There was, however, no data on head injuries and concussion.They concluded that their included studies showed a trivial difference in injury rates between third and fourth generation artificial turf when compared with natural turf. Limitations of the study were accepted, including the need for longitudinal prospective cohort studies including an adequate number of teams, and controlling for confounding factors such as weather and gender etc, and I think that there were indeed a number of important limitations of the study such that it is perhaps difficult to draw conclusions based on the evidence we have.

For me, the jury’s still out on the issue of injury risk with the newer artificial playing surfaces, but the traditionalist in me still thinks that soccer was meant to be played on a natural surface. Even if the risk of injury is, in time, proved to be no greater on an artificial surface, having watched soccer played on 3rd generation pitches and having played on them myself, I can say that from my point of view it never really looks or feels the same.

For me, the jury’s still out on the issue of injury risk with the newer artificial playing surfaces, but the traditionalist in me still thinks that soccer was meant to be played on a natural surface. Even if the risk of injury is, in time, proved to be no greater on an artificial surface, having watched soccer played on 3rd generation pitches and having played on them myself, I can say that from my point of view it never really looks or feels the same.

What do our readers think?

Should we entertain an expansion of artificial playing surfaces? If so, should that be just within specific sports? How do you think that we should assess injury risk on these surfaces and do you think that the effects seen would be different in different sports?

CJSM would like to hear your thoughts.

References :

Ekstrand J, Nigg BM. 1989. Surface-related injuries in soccer. Sport Med 8(1):56-62

(Images of (1) modern artifical turf diagrammatic, (2) side view of artificial turf, and (3) Aspmyra, Norway taken from Wikimedia)